This isn’t activism, it’s duty of care: What three recent reports tell us about climate change, young people, and responsibility in education: PART 3

This post uses the Count Your Carbon 2026 statistics as its evidential spine, and explicitly links back to the safeguarding framing established earlier in the series.

Schools are not neutral

What school carbon data reveals about responsibility, modelling, and care

In the previous post, I started where safeguarding always should: with children.

That post focused on what the Children’s People and Nature Survey tells us about young people’s emotional connection to nature, and the uneven access to protective factors across income, disability, ethnicity, and place. This post turns the lens in a different direction – not to blame, but to render visible something we often leave unexamined:

The institutional systems children move through matter just as much as the messages we give them.

To explore that, I want to sit carefully with the findings of the Count Your Carbon: Measuring the Carbon Impact of Schools in England (2026) statistics report.

What this data actually is

Before interpreting anything, it’s important to be clear about what Count Your Carbon represents. The 2026 statistics report analyses greenhouse‑gas emissions data from around 1,600 schools in England that completed carbon footprint calculations during the 2024–25 academic year. The figures are self‑reported, preliminary and explicitly described as indicative, not audited totals.

So it is not a league table, nor a compliance tool. And certainly not to be taken as a moral scorecard. It is, however, the first large‑scale attempt to describe where emissions in schools actually come from. That alone makes it worth taking seriously.

The headline figures people often miss

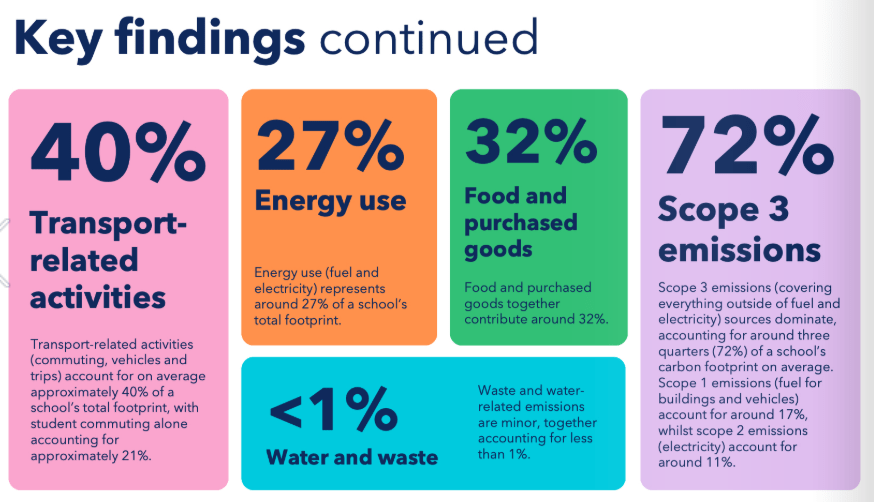

When schools talk about carbon, conversations often gravitate quickly towards recycling, switching lights off and pupil behaviour. But the data does not support that focus. Across participating schools, Count Your Carbon shows that:

- Average annual emissions sit in the hundreds of tonnes of CO₂e per school

- Around 72% of emissions fall under Scope 3

- Transport alone accounts for roughly 40% of emissions

- Food and procurement together contribute around a third

- Waste and water, by contrast, account for less than 1%

In other words, the overwhelming bulk of emissions connected to schools arise from structural, systemic decisions such as how pupils and staff get to school, how food is sourced and prepared, what goods and services are procured and how buildings are designed and heated.

Quite clearly, very little of this is under the direct control of children. So why is taking climate action often framed as an equal responsibility of everyone, espeically the students? More on that in a moment…

Structural differences matter

One of the most important – and least sensationalised – aspects of the data is how emissions vary by context. The report shows that:

- Rural schools have higher per‑pupil emissions than urban or suburban schools, driven largely by transport distances and car dependency

- SEND schools have significantly higher per‑pupil emissions, reflecting smaller cohorts, higher staffing ratios, specialist equipment, and transport needs

This is not evidence of inefficiency. It is evidence of structural constraint. From a safeguarding perspective, this matters because it makes one thing very clear, that carbon impact is not evenly distributed, and neither is responsibility. Any narrative that treats emissions as a simple outcome of individual or institutional “choices” collapses under even brief contact with this data.

Why this is a safeguarding issue, not a sustainability one

It would be easy to file this data under “sustainability strategy” and move on. But if we take safeguarding seriously – especially the emphasis on contextual and environmental factors – then this information has wider implications. Children do not encounter climate issues in the abstract. They encounter them through:

- school travel routines

- lunch queues and food choices

- conversations about “doing your bit”

- the hidden curriculum of what is normal or expected

When those everyday systems carry a substantially larger carbon footprint than pupils can influence, the way responsibility is communicated becomes critical.

The emotional underside of “do your bit”

This is where this post connects back to the People and Nature Survey, and to earlier work on eco‑anxiety. When children care deeply about the natural world, are told climate change is serious but see adults and institutions reproducing high‑carbon systems, while being asked to modify their own behaviour then the risk is not disengagement. The risk is confusion, guilt, and misplaced responsibility.

Count Your Carbon does not measure emotional impact. But combined with what we know about children’s nature connection and wellbeing, it helps explain why some young people report feeling responsible for problems they had no hand in creating.

Safeguarding is not just about preventing direct harm. It is also about avoiding unreasonable psychological burden, i.e. promoting protective and preventative factors.

What this data does not mean

It’s important to put firm boundaries around interpretation. This data does not mean that schools are failing morally and that staff should feel ashamed. And clearly it shows that pupils shouldn’t feel complicit and that a school should strive for perfection.

We have to bear in mind that most schools operate under severe budget constraints and transport infrastructures they cannot redesign. They utilise procurement frameworks they do not control and in almost all cases use buildings they did not choose.

The data simply shows where responsibility cannot reasonably be individualised.

What it does call for: institutional honesty

If we accept that institutions shape children’s lived experience, then safeguarding requires consistency between what we explain to young people, what we ask of them and what we model systemically.

That might look like being honest about where emissions actually come from and avoiding guilt‑laden behaviour messaging. Staff across the school, not just teaching staff, need to be able to explicitly identify constraints and trade‑offs, but there is an opportunity for framing action as collective and long‑term, not individualised and immediate. This is where the DfE’s Climate Change and Sustainability Education Strategy comes in handy, and can be promoted and planned for through a school’s Climate Action Plan.

In short, it is not about lowering expectations. It is about aligning ethics with evidence. I want to be explicit here: this is not a critique of individual settings. It is a critique of a narrative that places moral weight on pupil behaviour while ignoring institutional structure.

If safeguarding means anything, it means recognising when responsibility is being misplaced – even unintentionally.

Joining this to the bigger picture

In the first two posts, I argued that children already care deeply about nature, access to protective factors is unequal and emotional stakes are high.

I hope that this post adds another layer, demonstrating that institutions materially contribute to the risk landscape, and children move through those systems daily. And that we must be aware and reflective about the way we talk about responsibility can either help or harm.

The next post will widen the lens again – not to escalate, but to contextualise – by looking at what it means for educators when ecological risk is formally recognised at national level, as set out in the recently released national security assessment. Because safeguarding doesn’t end at the school gate. And increasingly, neither do the risks our students are navigating.

Next: Part 4 – When ecological risk becomes a planning assumption – reading the national security assessment carefully

Subscribe to be alerted when the next post in the series is published.

One thought on “Schools are not neutral: What school carbon data reveals about responsibility, modelling, and care”