This isn’t activism, it’s duty of care: What three recent reports tell us about climate change, young people, and responsibility in education: PART 2

Safeguarding work, when it is done well, always starts in the same place: with children’s lived experience, not adult abstractions.

In the introductory post to this series, I set out why I’m taking time to work carefully through three recent reports rather than rushing to conclusions. This post begins with the one that speaks most directly to children’s everyday lives: The Children’s People and Nature Survey for England (2025) published by Natural England.

The survey does something important: it tells us how children already relate to nature, how they feel about it, and how uneven those experiences are. If we are serious about duty of care in a changing world, that matters.

What the survey actually tells us

The People and Nature Survey captures responses from children aged 8–15 across England, exploring:

- time spent outdoors

- access to green and natural spaces

- perceptions of quality and safety

- enjoyment of nature

- degree of “nature connection”

One headline finding has been widely shared:

93% of children say being in nature makes them happy.

That is a remarkably high level of agreement, and it has been consistent across recent survey waves. More quietly, the survey also shows that:

- reported nature connection has increased year‑on‑year since 2021

- children overwhelmingly value access to natural spaces

- most children want to spend more time outside

Taken together, this suggests that nature is not peripheral in children’s lives. It is already emotionally salient.

Before going further, it’s important to name the limits of the evidence. The survey does not seek to prove that being in nature prevents mental ill‑health or that a lack of access to nature causes anxiety. It certainly doesn’t infer that children who feel connected to nature are better equipped for climate impacts

Those claims may be explored elsewhere in the research literature, but they are not conclusions of this survey. (In my summary article at the end of this series, I will combine the findings of this report with academic research that does explore those links). Staying within the evidence matters, especially for educators who have seen too many moralised or sensationalised claims made on children’s behalf.

What is clear: access is unequal

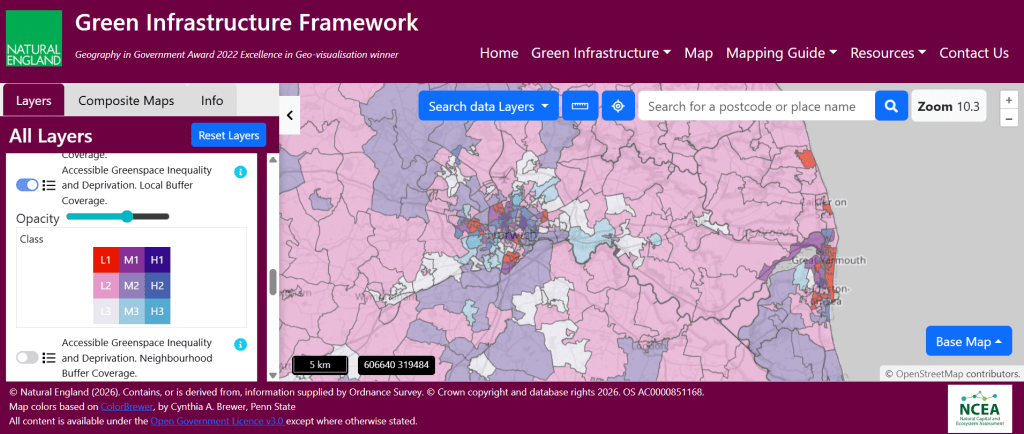

Where the People and Nature Survey becomes particularly important for safeguarding is in what it reveals about who has access, and who does not. The data shows clear differences linked to household income, disability, ethnicity and whether children live in urban, suburban, or rural areas.

Children from lower‑income households, children with disabilities, and children from some ethnic minority backgrounds report:

- less frequent access to natural spaces

- fewer opportunities to visit high‑quality outdoor environments

- higher reliance on school time for outdoor access

This is not a claim about individual families or choices, but instead reflects structural inequalities in housing, planning, transport, and access to safe spaces. From a safeguarding perspective, this matters because it tells us that protective factors are unevenly distributed before we ever get to curriculum content.

Why emotional salience matters for educators

One of the most important things the survey reveals—without ever naming “climate”—is that children already care. Nature is associated with happiness, freedom, play, calm and social connection. That emotional connection exists regardless of whether a child can articulate a scientific explanation of climate change, biodiversity loss, or sustainability.

This has two implications for educators and youth workers:

- Climate‑related topics will never be emotionally neutral even when we think we are teaching “just the facts”, children bring existing feelings, attachments, and concerns into the room.

- Careless handling risks harm through overwhelming narratives, guilt‑laden language, or abstract catastrophe framing which lands differently for children whose experiences of nature are shaped by inequality or insecurity.

This is not an argument for avoidance. It is an argument for care.

Where safeguarding comes in

Safeguarding is often misunderstood as something that only activates when harm is visible. In reality, safeguarding frameworks are built around foreseeable risk and identifying vulnerability and protective factors. Statutory duty is clear on early help and prevention and briefs educators on contextual influences outside the home. The People and Nature Survey contributes to this picture by showing that:

- nature is a meaningful protective factor for many children

- access to that factor is not equal

- school time is often a key point of access, especially for the most vulnerable

That does not mean schools must “fix” inequality, but it does mean schools cannot pretend those inequalities are irrelevant when they engage with climate, environment, or wellbeing.

Climate anxiety without overstatement

I’ve written extensively elsewhere about eco‑anxiety and climate distress, so I’m not going to rehearse that literature here. What matters in the context of this survey is something narrower and more defensible:

Children’s emotional relationship with nature exists first. Concerns come second.

That flips a common assumption on its head. Children don’t become anxious because adults tell them climate change is serious. Many are already attached to places, animals, and outdoor experiences that feel precarious or unequally accessible. Literacy, when handled well, can reduce confusion and fear. Handled badly, it can amplify them. That is a professional judgement issue, not an ideological one.

Why this isn’t “just geography”

It would be tempting to relegate all of this to the Geography classroom. That would be a mistake. In my mind, the Children’s People and Nature Survey has implications for tutors and pastoral staff, PSHEE and RSHE leads, SEND teams, youth workers and senior leaders responsible for whole‑school culture, to name but a few.

Any professional working with children who experiences heightened worry, expresses loss or grief related to place, or shows withdrawal from previously enjoyed outdoor activities is already encountering the edges of this issue. That does not require every adult to become a climate teacher. It does require shared awareness. Indeed, a nuanced and reflective reading of this survey should inform an education setting’s Climate Action Plan, where it can be a synergetic approach linking the action pillars of adaptation and resilience, biodiversity and climate education & green careers.

Holding the line carefully

There is a risk, whenever children’s wellbeing enters the conversation, of sliding into sentimentality or moral urgency. And while I am someone known to be passionate for a cause who wears their over-bearing sense of injustice on their sleeve, I want to be clear that here I’m arguing for neither. The survey does not call for panic nor demands radical change. And it certainly doesn’t accuse schools of failure. What it does do is quietly undermine the idea that children are emotionally disengaged from environmental issues, or that this is something adults are artificially imposing on them.

Children already know this matters.

Our responsibility is to decide whether we respond with literacy, care, and honesty—or leave them to make sense of it alone.

In the next post, I’ll turn to a less comfortable part of the picture: what school carbon data tells us about institutional responsibility, fairness, and the limits of behaviour‑based messaging.

Because safeguarding only works when we’re prepared to look at our own systems, not just children’s responses.

Next in Part 3: Schools are not neutral – what school carbon data reveals about responsibility and care

Subscribe to be alerted when the next post in the series is published.

Thank you for putting this series together, Kit. There are so many important points covered this post alone. In some ways we can say ‘the evidence speaks for itself’ and survey data is of course super useful for identifying trends, but this also helps to identify important areas for more in-depth, qualitative research to be done with children and young people and the important adults in their lives – research that doesn’t fear but can explore and unpack the emotions that we all have towards nature and the ways it and we are being affected by the climate crisis (which, as you’ve pointed out above, are structurally unequal). I love the point about the emotional relationship to nature that we all have being the starting point, and climate anxiety and related emotions being something that stem from that, rather than introduced through being taught about climate change. This is a great counter-argument to people who say we should avoid making children anxious by avoiding climate change as a topic. Something I’ve been thinking about more recently is the way that climate anxiety is often presented as ‘children’s’ problem in an infantilising way, when actually there is a lot of research showing that it affects us all (adults too) and is a logical response to seeing the impacts of climate change, and the frustration of not seeing action taken where it is needed. Keep the posts coming – I can’t wait for the next one!

LikeLiked by 1 person