This isn’t activism, it’s duty of care: What three recent reports tell us about climate change, young people, and responsibility in education: Final PART (5)

Across this short series, I’ve worked carefully through three recent pieces of evidence:

- how children experience and value nature

- how school systems materially contribute to environmental risk

- how ecological instability is now recognised at national planning level

None of these documents tell educators what to do or prescribe curriculum models, training programmes, or timelines. And yet, taken together, they change something fundamental: what it is reasonable to look away from. This final post is not about dramatic solutions or heroic leadership. It is about ordinary professional responsibility in a changed context – particularly for those of us who work with children and young people.

Re‑stating the evidence

Before talking about responsibility, it’s worth restating what this series has shown.

- Children already care about nature (Part 2).

The Children’s People and Nature Survey shows overwhelmingly positive emotional relationships with nature, alongside unequal access to the very experiences that support wellbeing. - School systems and structures are part of the problem – and the context (Part 3).

The Count Your Carbon data shows that most emissions connected to schools arise from systems children do not control, and that those impacts vary structurally by place and need. - Ecological risk is now officially foreseeable (Part 4).

The National Security Assessment frames biodiversity loss and ecosystem degradation as long‑term risks to food, health, and societal stability, without certainty about timelines but with high confidence in direction of travel.

Safeguarding rarely arrives with sirens

One of the difficulties with climate‑related issues in education is that they don’t conform to familiar safeguarding patterns. This is why it is taking me years to make the case that school leaders and policy makers should be treating climate change as a safeguarding issue. There is no single incident. No immediate disclosure. No neat threshold at which action becomes mandatory.

Instead, we see cumulative pressure, uneven vulnerability, an emotional load without obvious cause, and questions children ask that don’t have simple answers. Safeguarding policy already recognises this kind of risk in other domains such as online harms, radicalisation, contextual abuse and mental health and wellbeing. Climate and ecological instability increasingly sit alongside these – not because educators are responsible for causing them, but because children experience them.

Literacy as a protective factor

Throughout this series, I’ve been careful not to frame climate literacy as a moral or political stance, and to set aside my passionate advocacy for climate activism. In safeguarding terms, literacy is protective because it reduces uncertainty, helps distinguish credible information from misinformation, prevents catastrophic thinking rooted in partial understanding and allows proportionate emotional responses.

Poor literacy, by contrast increases confusion, amplifies fear and shifts responsibility onto individuals without agency. It will be counter-productive to suggest that we need “more content” or “more training”. It is an argument for careful framing, honest limits, and contextual understanding.

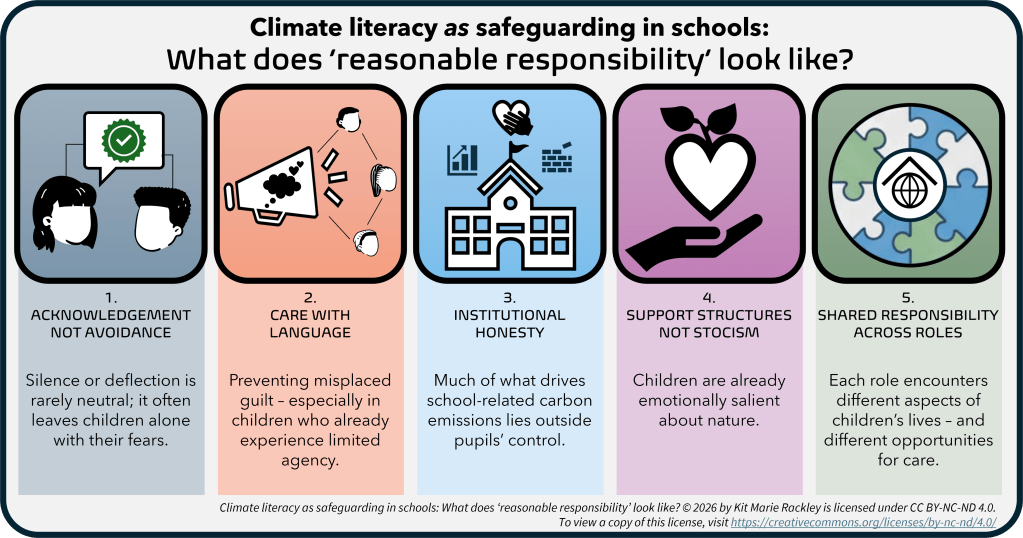

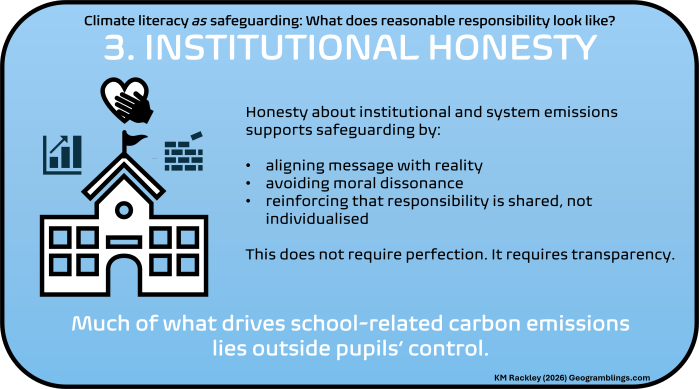

What reasonable responsibility looks like

I’m steadfast and resolute in my arguments that, as an educator community as a whole, we have to take responsibility. However, pulling on my experience as an ex-teacher who remains deeply embedded in the education sector, I am acutely aware of the institutional, operational and resource constraints.

It is unreasonable and impractical to say we must turn every lesson into a climate intervention, espeically in ways that appear to ask children to carry the weight of geopolitical or ecological failure. A recent government report on mental health impacts from climate change recognises with high confidence that this feeds anxiety in children.

We also need to avoid collapsing safeguarding into activism – although climate change is not explicitly referenced in statutory guidence, it still gives us plenty of scope to work with. For instance, we can infer from safeguarding practice that demanding emotional resilience without support is not acceptable. Finally, we should not hold individual educators morally accountable for systemic problems.

Those moves are ethically dubious and professionally unsound. Grounded in the evidence explored across this series, reasonable professional responsibility starts to take a fairly modest – but meaningful – shape.

1. Acknowledgement, not avoidance

When children raise concerns about climate, environment, or future uncertainty, educators respond better by:

- acknowledging seriousness without dramatics

- naming uncertainty openly

- validating concern without personalising blame

Silence or deflection is rarely neutral; it often leaves children alone with their fears.

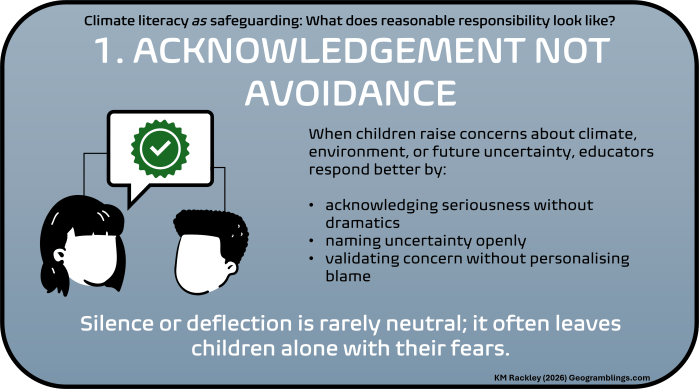

2. Care with language

As I’ve argued elsewhere, language matters enormously.

Moving away from:

- “you should”

- “your responsibility”

- “do your bit or else”

towards:

- “systems”

- “collective action”

- “levels of influence”

helps prevent misplaced guilt – especially in children who already experience limited agency.

This matters even more when institutions themselves remain structurally constrained.

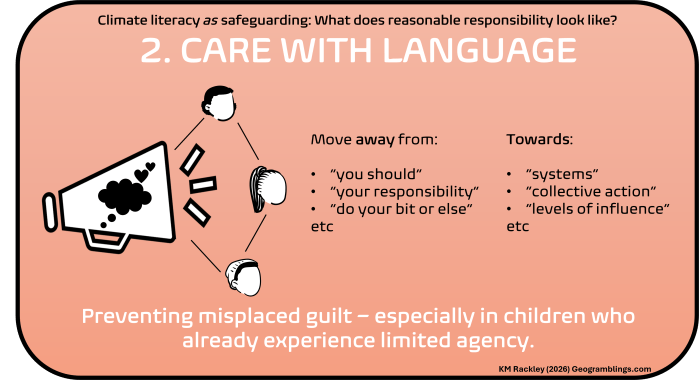

3. Institutional honesty

The Count Your Carbon data makes something unavoidable:

Much of what drives school‑related carbon emissions lies outside pupils’ control.

Honesty about that fact supports safeguarding by:

- aligning message with reality

- avoiding moral dissonance

- reinforcing that responsibility is shared, not individualised

This does not require perfection. It requires transparency.

4. Support structures, not stoicism

The People and Nature Survey shows how emotionally salient nature already is for many children.

Safeguarding responses should therefore include:

- awareness of climate‑related distress

- clear referral pathways

- space for reflection and reassurance

- access to outdoor experiences where possible

Not every concern needs escalation – but unacknowledged distress rarely resolves itself.

5. Shared responsibility across roles

Nothing in this series suggests climate literacy is “owned” by geography.

Responsibility is distributed across:

- tutors and pastoral staff

- SEND professionals

- PSHE and RSHE leads

- youth workers

- senior leaders

- safeguarding teams

Each role encounters different aspects of children’s lives – and different opportunities for care.

NB: The full evidence base for these five ‘reasonable responsibilities’ can be found as a downloadable PDF at the end of this article.

Why this isn’t about courage or virtue

It would be tempting to end this series with a rousing call to “be brave”. But bravery is not the issue here as the evidence does not demand heroism. It demands competence. It demands reading risks accurately, enabiling us to respond proportionately. And perhaps most importantly, it enables us to avoid harm while doing good.

Safeguarding has never been about having all the answers. It has always been about taking responsibility for what we know. Equally, what hasn’t changed is the core purpose of education: to support children’s learning, wellbeing, and development. But what has changed is the context in which that work takes place:

- environmental risk is more visible

- uncertainty is more present

- emotional load is more unevenly distributed

The three reports explored in this series don’t ask educators to do more than is reasonable. They simply narrow the space in which inaction can be defended.

Closing the series

I’m conscious that my determination to constantly write critically about climate, safeguarding, and responsibility has, and will continue, to make people defensive. That’s never been my intention, and I hope that how I’ve gone about writing this series demonstrates there is no pointing out failure, neglect, or blame. For my part, I feel is it my responsibility to shed light on the fact that we are operating in a professional landscape where children are paying attention, risks are formally recognised and institutions shape experience more than we often admit.

Climate literacy, handled with care, now sits squarely within duty of care. Not because it is urgent, and certainly not because it is fashionable. But because it is already part of the world our students are growing up in.

And safeguarding, at its best, has always been about meeting children where they are – not where we wish the world still was.

All posts in this series:

- Part 1 (Introduction): This isn’t activism – it’s duty of care

- Part 2: Children already know this matters

- Part 3: Schools are not neutral

- Part 4: When ecological risk becomes a planning assumption

- Part 5: What reasonable professional responsibility looks like now

- Evidence base for the five ‘reasonable responsibilities’: DOWNLOAD PDF ⬇️

Citing this work:

APA: Rackley, KM. (2026, February 1). Climate literacy as safeguarding: What reasonable professional responsibility looks like now. Geogramblings.com. https://geogramblings.com/2026/02/01/climate-literacy-as-safeguarding-what-reasonable-professional-responsibility-looks-like/

Harvard: Rackley, KM. (2026) Climate literacy as safeguarding: What reasonable professional responsibility looks like now. https://geogramblings.com/2026/02/01/climate-literacy-as-safeguarding-what-reasonable-professional-responsibility-looks-like/.

MLA: Rackley KM. “Climate literacy as safeguarding: What reasonable professional responsibility looks like now.” Geogramblings.com, 1 Feb. 2026, geogramblings.com/2026/02/01/climate-literacy-as-safeguarding-what-reasonable-professional-responsibility-looks-like.

One thought on “Climate literacy as safeguarding: What reasonable professional responsibility looks like”