I’m a football fan. I’m an England fan. I’m an intersectional feminist. I’ve been dubbed a ‘social justice warrior’ (that’s a badge of honour). I’m a member of the LGBTQ+ community.

Needless to say… I’m conflicted.

But I’m also a geographer, so that gives a hook and lens to tackle this (excuse the pun!). I cannot hope to cover the myriad of issues in any detail with any justice, so this post is going to be a mixture of personal opinion (mostly as a member of the LGBTQ+ community), some things to for educators to think about, and some signposting to various articles and opinions. Stick with it. Read, think, reflect, share. And at the end of this post there will be something you can download to play around with yourself or with students.

Desert Rose-Tinted Glasses? Looking back at looking ahead to Qatar 2022

Twelve years ago, Qatar were controversially awarded the football World Cup by FIFA, and the controversy continued ever since. I, like so many Geography teachers, jumped on this as a learning opportunity. Looking back at the resources that I created (below), I attempted to highlight the issues surrounding human rights alongside logistical controversies such as the climate and resources. Since then, having been a member of groups such as Decolonising Geography, and having conversation with folks from a range of perspectives and backgrounds, I certainly would approach this differently.

Here is the resource, and you are very welcome to critique it and think about how it could be done better. Also, has anything changed significantly in the 6/7 years since I made it?

One of the most powerful things about Geography is the subject’s ability to tackle controversial issues. Other than the awarding of the competition itself, attention has been drawn to other issues such as migrant worker rights and women’s rights. There is much commentary out there such as this summary article from NPR which references a number of different sources, for instance. Earlier this year for the Coffee & Geography podcast, I spoke to Emily Butler, a British Geography Teacher living in Qatar who gave some interesting perspectives. It is definitely worth a listen, with focus on the World Cup from timestamp 27:15.

LGBTQ+ RIGHTS: beyond the Bucket hats and armbands

I skipped over the issues above as there is plenty of further reading out there, and many voices of expertise, authority and experience out there – which I am not one of them. However, when it comes to LGBTQ+ rights I certainly can give a op-ed based on being an LGBTQ+ football fan.

To first state off-the-bat (or off-the-boot, if you like!), I find it intensely infuriating and upsetting that the existence of folks like myself are seen as a political or controversial issue in itself. The fact that there has been so much more visible debate about whether team captains should wear the ‘One Love’ pride armband or not, rather than the issue of LGBTQ+ and other rights itself is, well, frustrating to say the least.

I’ve always found it quite hypocritical for the organisers of major tournaments and events to one hand claim that global sport brings people together and celebrates diversity, and then on the other demonstrate restraint and conformity. In my view, it is these executive and top-level decisions by people of privilege that make an issue political.

Equaldex have created a policy and law-based index of LGBT rights across the world. It is worth having a look at both their methodology and openness to scrutiny (including the ability to report inaccuracies).

Out of 198 countries, Qatar ranks 181st with a score of 14/100. This is solely based on the legal situation in the country. The report states:

Qatar is a conservative Muslim country and homosexuality is illegal. Non-Muslims are punished with fines and up to 7 years imprisonment, and for Muslims, they can technically be punished with the maximum being death under Sharia law. There is, however, very limited evidence that this law is enforced.

Qatar’s laws and cultural norms are based on traditional gender roles and norms. Homosexuality is seen as a violation of these norms. LGBTQ+ individuals face harassment, discrimination, and violence in Qatar, and are not allowed to engage in same-sex sexual activity.

Despite any one persons or one cultures belief, LGBTQ+ people are real and exist. This is an undeniable fact. So I would challenge anyone who things it is not an issue worth discussing, or say it is ‘virtual signalling’ to raise awareness etc to think deep. If a major sporting event like a World Cup is not the right opportunity to speak out and address inequality and injustice, then when is!?

And if you still aren’t convinced, I’d like you try a little hypothetical. Re-read the statement from Equaldex about Qatar above again. But this time, swap out the words in bold for words like ‘black’, ‘Jewish’, ‘female’, ‘disabled’ and some example of cultural expression of identity. At what point does it stop sitting comfortably with you? Would you then decide to speak out or draw attention?

The World Cup of Development (or, the problem with development indicators part 1)

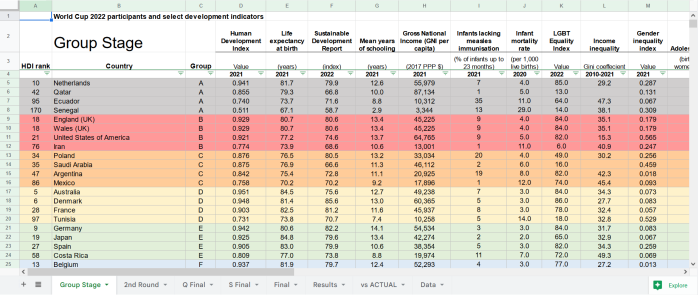

Ok, let’s take a short break from the necessary heavy thinking and self-reflection and be a little more light-hearted for a moment. Has there been any correlation between global development statistics and the results in the tournament so far? Like the last two major football tournaments (2018 & 2020), I have created a spreadsheet for Geography teachers to take advantage of the football hub-bub that usually overtakes classrooms.

On that spreadsheet, there is a tab (“vs ACTUAL”) showing which development statistics that I used most match the actual results of the World Cup tournament so far. First, the group stages. Which of the selected development statistics did I use most closely matched up with how the teams ranked by the end of the group stage? Out of the eight groups, none ended up matching their ranking of the supposed ‘gold standard’ of development statistics, the Human Development Index. This is not a great start for development indicators being a measure of footballing success! So, I had to play around to find rankings that matched football reality.

For the second World Cup in a row, England’s group (B) didn’t quite match any of the chosen development statistics. ‘Urban population’ came closest, with England and the USA’s stats being almost the same. The other group that I couldn’t find a match with what I had was Group C – but in the world of development, Argentina and Poland would have been the top two with renewable energy consumption, so that was chosen. The Netherlands won Group A by virtue of the smallest income inequality; France simply bested their group (D) by the sheer number of people (population); Japan outlived their rivals in Group E by topping life expectancy just ahead of Spain, knocking Germany out; Morocco were the surprise winners or Group F but perhaps not if you take the fact that they have the latest Earth Overshoot Day of the bunch. Brazil also played the ‘urban population’ game, coming out comfortably on top in Group G; and finally Portugal and South Korea edged out of Group H thanks to a better Sustainable Development Index.

The graphic above can lead the way to some interesting classroom discussions either for a form time or perhaps a starter activity. Some ideas:

- Why does the level of development (HDI rank) appear to have little bearing on the outcome of the groups?

- Which development statistics used in the graphic are likely to have a greater (or lesser) bearing, if any, on the performance of a country in sport?

- What factors other than development might influence the performance and results of sporting fixtures?

- How might the fact that most international players play their club football in advanced countries (ACs)/higher income countries (HICs) influence the outcome?

- Which statistics used are a more or less reliable as a measure of development?

When ranking the teams by HDI, however, you do see that the more developed a country is, they are more likely to make it out of their groups, but it’s not a given. Indeed, for Morocco and Senegal (or usually, historically, for any African team) to make it out of the group stage is always a pleasant surprise – in footballing terms).

Then onto the Round of 16, the first of the knockout stages. Was there more or less of a link with a country’s level of development and success? While in a straight knock-out it was easier to find at least one development statistic which favoured the actual victor. However, only three of the results matched HDI rank, the Netherlands beating USA, France brushing aside Poland and England defeating Senegal.

While it was easy to find a winning statistic for countries closely ranked in HDI, it took a bit more of an effort to find one for countries with a bigger gulf in development. Replacing goals with development, Argentina were never really in trouble against Australia thanks to greater representation of women in parliament; the only way Croatia could really overcome Japan was to play their ‘Earth Overshoot Day’ card to draw level and then prevail in the penalty shootout; Brazil swept past South Korea with little effort thanks to better LGBT equality; Morocco defied all the odds eventually taking apart favoured Spain thanks to a slightly lighter dependency ratio; finally, Portugal ran away with it against Switzerland thanks to renewable energy.

So, the big question… Do the development statistics provide a good omen for England in their upcoming quarter-final against France? They seem pretty similar with France ranked 28th and England (UK statistics) 18th in HDI. Well, I have some bad news I’m afraid! For the selected statistics on the spreadsheet, France are better off in 15, while England/the UK are only better off in 12. That equates to a win for France by a single goal (1-0 or 2-1). Development statistics from the spreadsheet roughly equate to the following results for the other matches:

Netherlands 3 -1 Argentina

Brazil 1-2 Croatia

Portugal 2-1 Morocco

Although those results look rather possible, the good news for England fans is that development, on the whole, doesn’t have a huge influence over the result of a football match! Brazil is expected to get past Croatia, and Argentina can be unbeatable on their day.

decolonising development indicators (or, the problem with development indicators part 2)

The measurement of development in such a quantitative way is a product of a westernised, capitalist point of view. Supporting this is the fact that for so long, before the flawed ‘Human Development Index’ was developed, that the measure of a country’s economy (usually via Gross Domestic or Gross National Product) was considered the gold standard of measuring a country’s progress. But of course, such measures are ones of accumulation and acquisition. They are by definition and design inhumane. They count the wealth acquired (or lost) through historical- and neo-colonisation, and turn human effort, creativity, productivity into a cash-counting exercise. Some may argue that this is addressed by looking at the bigger issue, such as access to education, sanitation, water, healthcare etc. But again, all these are measured through a western lens.

For instance, to call an indigenous group which lives and thrives in harmony with nature as ‘underdeveloped’ or ‘uncivilised’ because they don’t have plumbing, don’t have synthetic mass-produced medicine and no school that teachers theory and fact derived from “‘civilised cultures”‘, misses the point completely and I would argue deeply harmful and offensive. How are we to say that the rest of the world must develop using a westernised model? Indeed, look where that has led us in terms of environmental and social issues…

Recently, I wrote an article published by Tutor2U regarding the need to re-examine how we think about sustainability in the tropical rainforest. My arguments and examples used are directly related to the ‘global development’ debate. Go check it out!

For further reading I would highly recommend Professor Morag Goodwin’s 2018 paper ‘The poverty of numbers: reflections on the legitimacy of global development indicators’. It really helped me to think about the nuances and proxies regarding why certain indicators having been used, leading to questions why therefore they are still in heavy use today. Also interesting is this summary and opinion piece by Shannon Paige published on Peace Direct, ‘COVID-19 has shown us how to decolonize international development’ which recognises the flaws and issues caused by western measurements.

Final thoughts

So, how would you de-colonise and de-westernise the World Cup spreadsheet? My insertion of the ‘Earth Overshoot Day’ measure is a small attempt on my part, recognising areas of the world which are living more within their means in terms of the earth’s resources. But even this is not that straight forward, as some regions may have a late overshoot day because of historical oppression, while over do so because they living more in tandem with nature. The indicator doesn’t differentiate.

What alternatives are there? What about any of these, are they examples of a different, more inclusive and representative way of measurement or just more of the same re-dressed? How would the World Cup play out with them?